Mint.com Tracks Two Million Users to Create Spending Index

When staff writer Sasha introduced Consumerism Commentary readers to Mint.com in 2007, I began to think about the power of massive consumer financial data. As more people signed up for this online service that connects directly to users’ credit card accounts and bank accounts, Mint.com, or any other similar services, would be able to analyze more accurate spending data than government surveys that rely on self-reported data, and possibly even industry surveys.

Now with 13 million users, Mint.com has penetrated mainstream culture beyond just techies, who love tracking information online, and personal finance lovers, who look for any tools available to help them manage their money. Of these 13 million users, 2 million have opted in to this program, allowing Mint.com to aggregate their transactions anonymously.

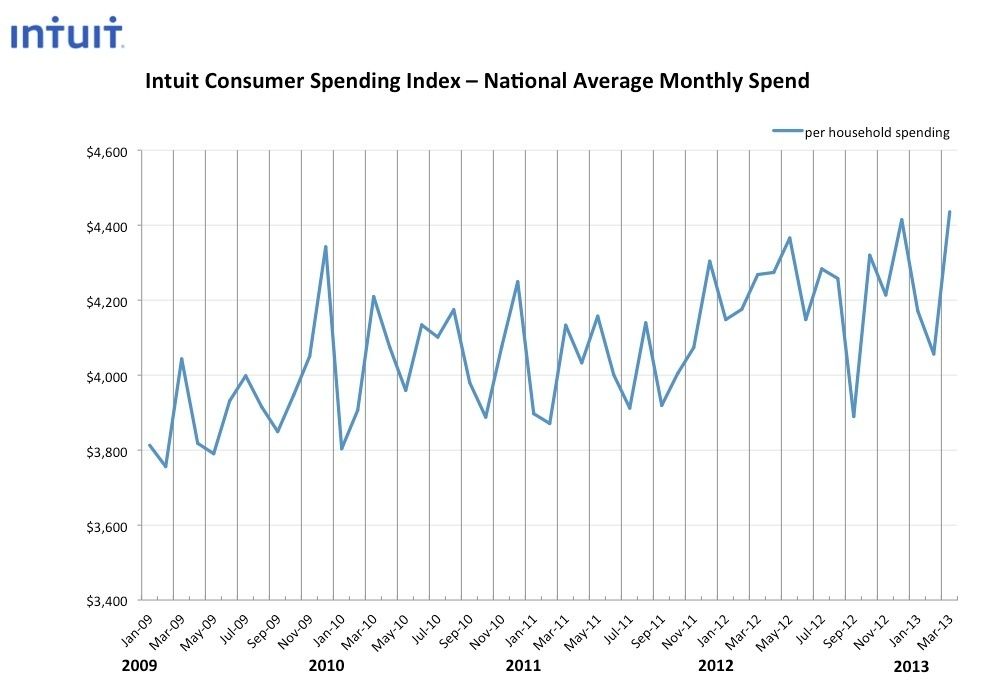

The company has now used the transaction data from this sample size of 2 million to produce what it’s calling the Intuit Consumer Spending Index. Intuit is the software company that now owns Mint.com. From the first quarter of 2009 to the first quarter of 2013, overall spending is up 9 percent, from $3,870 per month to $4,220 per month. Intuit announced its new index recently.

Because Mint.com categorizes every transaction and knows where its users live, the analysis of the data behind the index can go into much more detail. For example, in the District of Columbia, spending has increased 30 percent over the time period, much more than the 9 percent national average. Why has spending increased so much in the nation’s capital? The report from Intuit doesn’t say specifically, but the underlying data might have some clues.

The index can also describe spending by category within each state or nationally, and the information exists to explain why spending within a category has changed. For example, spending on groceries has increased 17 percent over the time period.

While an increase in food prices may contribute to some of that increase — although inflation is taken into account when calculating the index to reflect real changes in spending, not nominal changes — the transactions categorized as groceries indicate that more spending has shifted to boutique grocery stores like Whole Foods. 19 percent of grocery shoppers shifted to Whole Foods while spending at Safeway decreased by 3 percent over the same time period.

Mint.com also knows the ages of the 2 million users who have opted in to aggregation by sharing their personal demographics. For users aged 26 to 31, spending on healthcare increased 45 percent from 2009 to 2013, and the same consumers are also spending more at restaurants — an increase of 40 percent. The report also highlights different spending patterns between men, who spend more on entertainment, alcohol, and restaurants, and women, who spend more on clothing.

I had several concerns about the Intuit Consumer Spending Index.

- Is the 2 million user sample representative of the nation’s total population?

- What is the possibility that many of the transactions are categorized incorrectly?

- For people who use checks, how can Mint.com know the recipient of the payment?

Intuit handles the first problem my normalizing its sample against the government’s Current Population Survey. For example, if people aged 18 to 24 comprise 25 percent of Intuit’s data but only 10 percent over the overall population, Intuit’s data is weighted to reflect the actual composition of the population. Intuit performs the same reweighting along all its demographic measures.

One way the company tries to focus on accuracy by ignoring transactions over $100,000, which are often recorded as mistakes, not actual spending, and by validating their data against Census Retail Sales data. That doesn’t help in categories where people don’t typically pay with credit or debit cards, like spending on cars — maintenance, auto loan payments, etc.

Unfortunately, the raw data used to create the index does not seem to be available. I suppose that’s understandable, as Intuit is a business enterprise, not a government entity, but it doesn’t allow any deeper analysis by economists — or financial writers. We have to rely on the information Intuit chooses to disclose in its press releases and reports. The company’s team does seem to be accessible, so I’m confident that I can relay any questions to the company’s own economists should there be any, and if I wanted to write about spending in a specific category or in a specific location, I could get the data from Intuit to use in a story.

It’s probably been a few years since I’ve logged into the Mint.com account I created when the service became open to the public. It took me a while to log in because I couldn’t remember which email address I used to sign in — and I discovered by searching my email archives that it’s an email address I no longer use or have access to. After logging in, I saw that most of my accounts haven’t been updated in two or three years. I track my spending and investments with the desktop version of Quicken, so Mint.com never appealed to me much.

Checking my account profile, I see that at some point I provided basic demographic information about myself — now outdated — so in some way, my inaccurate data, both inaccurate demographics and missing transactions, was included in the aggregation that resulted in the Consumer Spending Index. According to the methodology, my information was likely just ignored, like many users who haven’t visited the website enough for there to be meaningful data.

Article comments

You could already do some of these comparisons using the trends feature. You could compare your spending against various demographics to see how average (or unique) you are in spending habits. This looks to just be a report based version of what you could already see.

I use mint & I love it. It’s great that I’m able to daily check my finances as well as set budgets & financial goals. Their blog is also very good.

I have not signed up for mint. I don’t know about anyone else, but this tracking has a “Big Brother” type of feel to me. I guess if you volunteer your demographics, you are okay with that. I’m just and old and wary soul….

I was wondering when they would get to this. They have so much useful data that it would be silly not to aggregate it and find trends. While I do think there will be mistakes in it due to how Mint classifies transactions, it will still be a pretty useful tool.

But also, the average Mint user might have changed. If they aren’t comparing the exact same pool of users from one year to the next, they aren’t actually getting a realistic glimpse into what the same people are doing with their money. Maybe more affluent people have started using Mint–from this data, we can’t tell.

That’s a valid concern, but it seems Intuit already took into account the changing nature of its user base. This is what it says in the document that outlines their methodology (which you can find by following the link to their announcement above):

Hmm. It may be valid or may not, depending how they do this. The best control would be looking at the exact same users over time, though, I believe.